Adam Grant, a professor of management and psychology in the Wharton School at my Alma Mater, the University of Pennsylvania, has an interesting column in the Times on raising creative kids. It’s a bit simplistic but that’s okay. How deep can you go when the paper won’t give you the 35,000 words you need?

Grant’s point is pretty straightforward. Most creative people come from homes where the structure was loose, the focus was on moral codes and the intense pressure to perform seen in many families was largely absent. In short, Tiger Moming may produce kids who are excellent musicians or superbly skilled at design and drafting but it doesn’t necessarily get you composers or break-through architects.

He also cited a survey comparing scientists who won Nobels with other scientists and the general public. The Nobelists were over twenty times more likely to have performed on stage, over ten times more likely to write poetry, plays or novels and twice as likely to play an instrument or compose music.

The foundations of creativity are complex and studied with well, creativity. A wander around Google Scholar will give anyone interested a feel for the more recent work.

All this got me into a bout of self-reflection. I think I’m creative. My research was kinda ‘breakthroughish’ in a modest way. I introduced a novel concept in cognitive psychology and saw it become the foundation of a series of insights in a variety of domains. It took some time for my empirical findings to be acknowledged and even longer for my theoretical model to be accepted which, in retrospect, isn’t surprising. I thought in ways compellingly different from my colleagues — so much so that they often had trouble getting their heads around what I was saying. It was frustrating but, in the end, satisfying.

I also had an endearing affection for “soft underbelly” of life — gambling, poker, horse racing, sports betting. I ended up penning three books on gambling and poker and writing several hundred columns for various gambling outlets, websites and magazines. Since retiring I’ve become the classic struggling writer who has managed to publish a novel and hopes to find the motivation to finish a second.

So I kinda fit Grant’s notions of a creative person — though still waiting for the Nobel Committee’s phone call… ; - ).

What intrigued me about Grant’s little essay was how closely his recommendations for nurturing creativity matched my upbringing and how my career was so off the standard road most of us middle-class kids were trained to walk. Yetta, my first-generation, Brooklyn-born, atheistic Jewish mother, was an artist.

She herself was raised in an orphanage when the family broke up, couldn’t afford the rent and ended up living for a time on the streets with her mother and two sisters. Remarkably, she loved the orphanage. She said it opened her to new people and ideas. When she was old enough she was sent out to be a house-keeper nanny to a wealthy family. While others might see this as something akin to indentured servitude, she saw it as another opportunity — to live in a new neighborhood, take their kids to museums, parks, eat new foods.

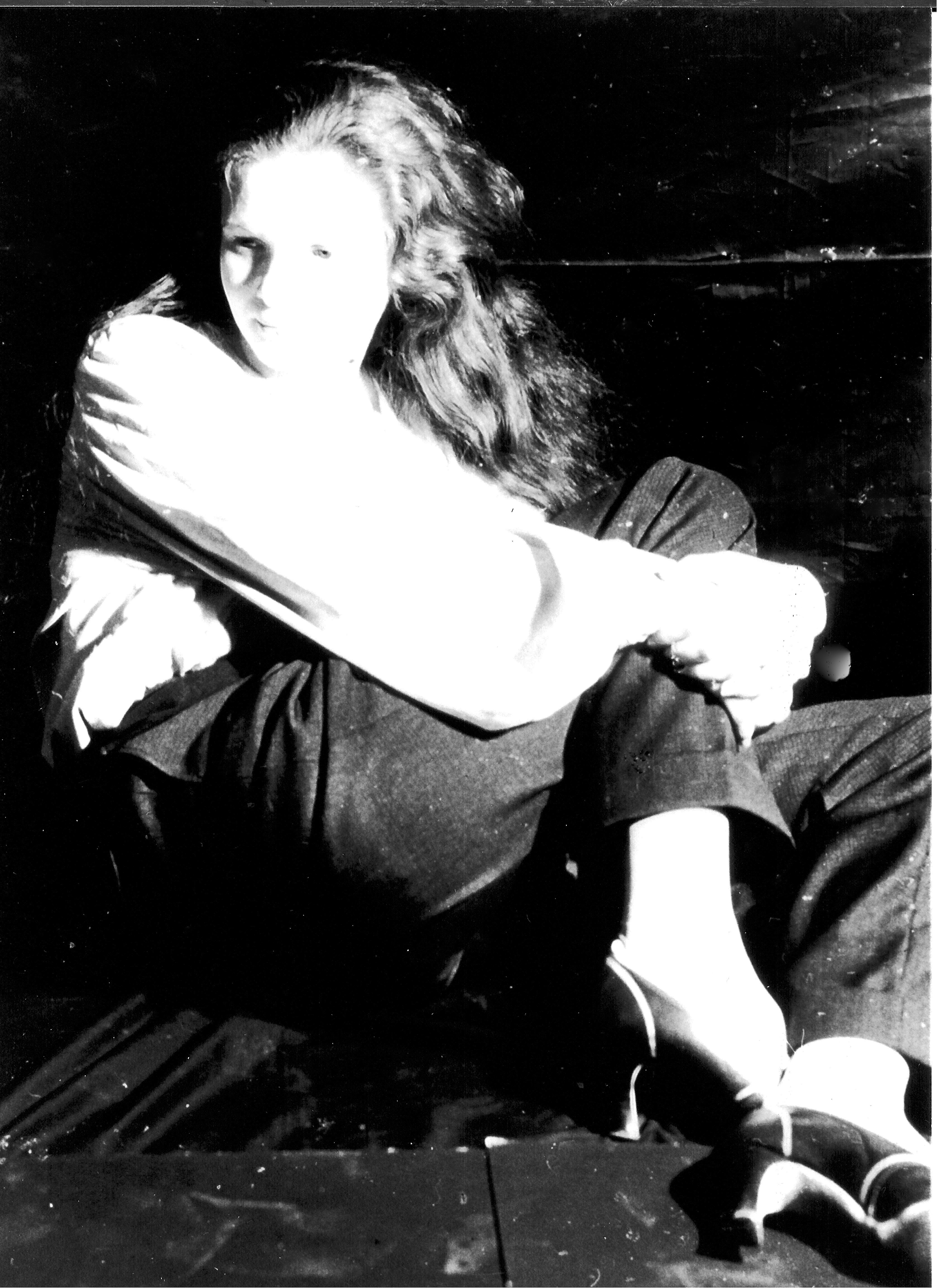

She became a reasonably recognized artist in and around Philadelphia with, at one point, two of her painting hanging in the Philadelphia Art Museum. Here are two photos of her taken in the early 1930’s.

But she was something well off the charts as a mother. Powerful, occasionally dominating, eccentric; with flaming red hair she would swoop through homes and galleries with her favorite purple cape overwhelming the unwary — not out of ego or insensitivity, it was enthusiasm for life bubbling over.

The home was just nuts. Nothing got done in anything like a routine way. She was a horrible cook — once buying a whole filet as a “special” meal for us and then roasting it for three hours because that’s how her mother cooked beef back in Russia. Her personal recipe for chicken soup began, “first open a can.”

My sibs and I sat down one day, cracked open a bottle of wine and asked the question: “Okay, how did you survive Mom?”

My sister laughed, “I just slammed down the gate to keep her out. It drove her nuts but it saved me.” She’s an accomplished cellist.

My brother nodded sagely, “Well, I saw this quiet, withdrawn chap over there (Dad) and realized he’d figured something out. Just let her do her thing. Nothing you do to control it will work.” He’s a recently retired psychiatrist who, last year, published a major book on autism and is, himself, embarking on a life as a short story writer (his stuff is pretty good).

Me? Hah. I was the oldest and my “solution” to Yetta was battle her at every turn, fight every move she made, carve out my own way of doing things and thumb my nose at her. We had some of the juiciest donnybrooks imaginable over art, music, politics, sex, marriage, relationships, money, religion. You mention it, we fought over it. We actually agreed on almost any topic but agreement was not part of our bargain. It just wasn’t any fun.

BTW, my father, an ophthalmologist and eye surgeon, was a quiet, unassuming and anxiety-ridden man — remarkably accomplished but unsure of himself, a constant worrier who saw monsters under every bed and demons in every closet. I loved him but much preferred the good ol’ knock-down dragged-out fights.

In retrospect I credit the whirlwind that spun around Mom for much of my creativity. I also “credit” her with the ragged path I took. I was a terrible student. I was suspended in high school, flunked out of Penn in my sophomore year, barely graduated with a 2.3 GPI after they, reluctantly, let me back in, and was only accepted into a single graduate program and that only because I worked with a famous psychologist who was a Brown graduate himself.

I was such a pain in the ass as a young professor that I was initially denied tenure despite having out-published all the members of the tenure committee combined and winning teacher of the year award. It took a year and a series of appeals to get that decision overturned. Amusingly, I was later elected head of the department, ran the doctoral program, the university named me to an endowed chair and the ASP, AAAS and the Fulbright Foundation all elected me Fellow.

But, you know, I’m still mildly ticked at a lack of recognition for some of my other little outbursts of creativity. I’ve published a novel theory of consciousness that has gone unacknowledged despite the fact that it makes provocative and nuanced arguments about evolutionary biology, cognitive psychology and the philosophy of mind.

I also put forward a novel theory of gambling that redefines the term, restructures the enterprise and has important implications for legal, legislative and ethical approaches to gambling. It too has received few if any citations.

But I’m used to this. Being creative is cool but it’s not always easy — especially in a field like mine. In physics or mathematics the equations are there, the numbers stack up. In psychology it’s more complex and change is often resisted. It took years for my work on the cognitive unconscious to be noticed too.

Here’s hoping I live long enough for the folks working in fields like the origins of consciousness and the theory of gambling to stumble across my stuff.

If not…Well, life’s like that and I can hear my mother’s voice: “It’s no skin off my nose. I’ve got a wood carving I’m really excited about and barely enough time.”